George Rochester was born in the Northumberland coastal village of Alnmouth on the 17th December, 1898. His father was the custodian of the local golf club. George was an avid reader as a youth enjoying such authors as Gunby Hadath and Talbot Baines Reed. In 1918 he joined the Royal Flying Corps and in August 1918 was sent to Xaffervilliers in France. Later that same month his Handley Page bomber was shot down but he was lucky enough to escape serious injury in the crash. After being taken prisoner Rochester was sent to various P.O.W. camps, ending up at Landshut - ironically the same place which held W.E.Johns, later to be the most famous of the writers about flying. Rochester was kept a prisoner until the Armistice and resigned from the R.A.F. in August 1921.

His first brush with literature came when he was eking out a living as a golf caddy. His short story called "The Funk" was accepted by Geoffrey Pocklington, the editor of the famous "Boy's Own Paper". Encouraged by this success, Rochester knuckled down to produce a full-length story. This was "The Flying Beetle" which was accepted by Pocklington and illustrated by H.L. Shindler. The character of Harry Davies, who was the "Flying Beetle" proved to be tremendously popular and Rochester discovered that he had the aptitude for writing about flying and that the public (in particular the readers of "B.O.P.") had an appetite for reading them. A whole flood of stories for storypapers and magazines then followed. However, his first work in book form appeared in May 1933. Later in 1936 John Hamilton Ltd. took the unprecedented step of publishing 16 of his books in one year !

During World War 2 Rochester joined the R.A.F.V.R. and served until 1944 when he was invalided out on health grounds. After the war his tremendous output continued and he wrote for both Hutchinson and Lutterworth Press. His work also thrived under many different pseudonyms such as Elizabeth Kent, Hester Roche and Alison Frazer. George E. Rochester died on the 23rd March, 1966, aged 68. He was survived by two daughters.

THE GLORIOUS 1930s:

Traitor's Rock 1933

The Black Pirate 1934

The Crimson Threat 1934

The Black Chateau 1935

The Black Squadron 1935

Captain Robin Hood, Skywayman 1935

The Flying Beetle 1935

The Flying Spy 1935

Adventures at Greystones 1936

The Air Ranger 1936

The Air Trail 1936

The Bulldog Breed 1936

The Black Hawk 1936

The Black Mole 1936

Brood of the Vulture 1936

Dead Man's Gold 1936

Despot of the World 1936

The Flying Cowboys 1936

The Freak of St Freda's 1936

Grey Shadow - Master Spy 1936

Jackals of the Clouds 1936

The Mystery of the Flying V Ranch 1936

Pirates of the Air 1936

Porson's Flying Service 1936

The Shadow of the Guillotine 1936

Wings of Doom 1936

The Trail of Death 1936

Derelict of the Air 1937

Scotty of the Secret Squadron 1937

Sky Pirates of Lost Island 1937

The Squadron without a Number 1937

Vultures of Death 1937

North Sea Patrol 1938

The Scarlet Squadron 1938

The Secret Squadron in Germany 1938

The Sky Bandits 1938

The Vultures of Desolate Island 1938

THE FORTIES AND FIFTIES:

The Flying Shark 1947

Phantom Wings 1947

The Black Bat rides the Sky 1948

The Lair of the Vampire 1948

Scourge of the Skies 1948

Sons of the Legion 1948

Wings of the Night 1948

The Return of Grey Shadow 1949

Tiger Hawk 1949

The Worst Squadron in France 1949

Haunted Hangars 1950

The Greystones Mystery 1950

The Moth Men 1950

The Black Wing 1951

Fledgling Wings 1952

Sprig Dawson: Pilot 1952

White wings and Blue Water 1952

The Black Octopus 1954

Secret Pilot 1954

Buzzards Roost 1955

Drums of War 1957

OTHER BOOKS :-

Christine, Air Hostess (as Mary Weston)

The Haunted Man 1951 (as Jeffrey Gaunt)

The S.O.S. Squadron (as Hamilton Smith)-

The Flying Fool (Undated)

Sealed Lips (as Elizabeth Kent)

Bitter Harvest (as Elizabeth Kent}-

The Night Hawks

SHORT STORY COLLECTIONS IN WHICH THERE ARE ROCHESTER STORIES:

Ace High, 1938

Air Adventures, 1938

Air Stories, 1938

Flying Adventures, 1936

Flying Stories, 1936

Flying Thrills, 1936

Out of the Blue, 1938

The Funk

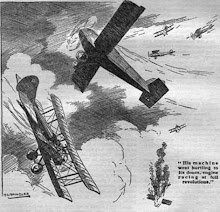

Rochester’s initial story about his series hero was called “The Funk”, and this was a very short tale about an incident during World War I. Already, in his first successful venture into commercial writing, Rochester displayed the gifts that turned his later offerings into adventures well above the standard of most of his contemporaries. The first of his talents was the ability to describe in convincing and upsetting detail the progress of an aeroplane through enemy fire as the pilot forces his way onward to deliver the bombs on target. Alongside the hero in the cockpit is Binks whose every feature proclaims the fear that has overwhelmed every normal desire to preserve his self-respect. Harry Davies has known from the moment that they were given the orders to set off and bomb the railway in Trier that the man beside him has lost his nerve. There is little Davies can do but fly on and hope that Binks will loose the bombs when the order is given . Pounded by the anti-aircraft guns and facing a stream of small arms fire, the pilot imagines the ‘plane falling to piece all round him. As Binks refuses to obey the orders to release the bombs, Davies realises that his observer has already cracked-up beyond repair. In the end somehow or other the two of them drop their deadly cargo. As Davies’ machine falls out of the sky he knows that Binks will never be of any use as a flier but then, it matters little, for death is the most likely outcome from the crash which will surely follow. Rochester has admirably created a vivid picture of both the hell of the sky around the plane and the seething cauldron of bitter feelings inside the cockpit. It is a very effective piece of writing.

But Rochester has not finished with us. Harry Davies wakes in hospital, badly burned but still alive. As the German medical staff point out, “For you the war is over…”. Eventually Davies discovers that the tightly bandaged figure in the next bed is Binks. It is difficult for the pilot to work out what feelings he should have for the man who seemed to let him down so badly. Binks becomes conscious and tries to make Davies promise that he will tell the exact truth of what happened when he gets home to England after the war. In particular Binks insists that the message of what he has done must be carried to his father. And then the awful truth emerges. There were only three survivors in the Binks family : Binks, his father and his brother. Before he left England he had just learned that his brother had been taken prisoner and was being held in Trier. Both Davies and Binks know that the Germans were in the habit of using their prisoners as hostage-shields, and that Binks’ brother would most likely have been placed near to the most prominent target – the railway section they had been sent to bomb.

All the readers’ thoughts are reversed and the so-called coward’s behaviour in the cockpit is now open to a new interpretation. When the Germans tell Davies that he was pulled out of the wreckage of his burning wreck of a plane by the courageous efforts of Binks the reader knows that the poor man’s character has been completely rebuilt. Surprise endings like this are always difficult to pull off successfully but Rochester accomplishes this one with some verve and skill. It is little wonder that the readers of Boy’s Own Paper in the late 1920s voted him their top writer and definitely the person whose stories they most wanted to see.

Ending it all. The Despot of the World

[To the right you see issue number 16 of 'The Boy's Wonder Library', no.16, dated 17th February, 1933. This miniature pocket library measured a mere 11 x 16 cm and ran to 64pp plus cover.]

Who could fail to be moved ? The prologue to “The Despot of the World” is no tame introduction to the characters, the places and the events that are about to unfold in the pages that follow. The opening words combine that note of melancholy and wonder that Browning captured in “Childe Rowland to the Dark Tower Came” and that Coleridge used to grip us in “The Rhyme of the Ancient Mariner”.

“Day is almost done, and shades of the coming night are creeping in across the restless sea to swathe in grey shadow the silent dunes of sand. As I sit here by my window I see again in the deepening dusk that strange fantastic company of Castle Grim.”

Is it a group of medieval knights setting off on some sinister but compelling quest ?

“They pass before me, a phantom host, but I can name them all: the cruel and merciless Zanderberg, warped of mind and body, yet brilliant of wit; the gentle Guillaume, scarred by the knout, crippled by the fetters, yet with the hint of gallant laughter in his weary eyes; the brutal Borstorge.”

As the narrator drifts into this dream of the past, he takes the reader with him until all the thoughts of the sad storyteller begin to group around his own “familiar friend” and a quest that was “the most perilous and most tragic of them all.”

And so a giant shadow already hangs over this story of the flying adventurer, Harry Davies, the Flying Beetle. The reader knows that, whatever difficulties are overcome and whatever triumphs are achieved, death awaits the hero. The book’s success lies in its tone – an impenetrable sadness that pervades it from the first. And, at the end, is also a turn of the plot that I dare not give away – a sacrifice that is both wonderfully upsetting and tragically uplifting.

Beverley, the storyteller, has enough horrific adventures of his own to make the reader forget for a while that is the destiny of the Flying Beetle that should be the centre of our concerns. The story opens in Alnmouth in Northumberland (Rochester’s own birth-place) where the message comes to Major Beverley from a ship’s captain who has docked in Amble . He has walked the six miles in a gale of wind and driving rain merely to deliver his urgent message. I have walked the very road he must have struggled along. I have seen the breakers smash up the beach in a storm. I have seen a lonely house that could have been Berverley’s own dwelling. It’s all clear to me.

To Danzig and then to Zilsen is the first lap of our narrator’s pilgrimage to Castle Grim, the particular dark tower of this story. In Zilsen Beverley is forced to wait for the Beetle’s message. It is a staging post in the journey and Rochester suddenly leaves his story behind for a while and takes us on a walk towards a place called Pillau. There he describes “an encampment of long, black huts.”

Beverley inquires of an old bearded man what place it was. It was the “lonely camp to which British officers and men had been sent when the tide of war was turning against Germany on the western front.” A footnote reveals that Rochester was a prisoner-of-war in this particular camp and he gives a chilling reminder of what it was really like “And here had been spent the long weary days, the endless shivering nights, until release had come.” It is clear that autobiography has escaped into fiction.

True, this episode does not develop the action of the story one jot but it does achieve something else. Its genuine feelings counter some of the more artificial aspects of his characterisation of a stereotypical bad German. It also introduces that prevailing environment of bleakness, chill and deadly cold that underline the misery and suffering that is to come.

Flying adventures in the form of aerial combats are here in two strong doses. A journey to the heart of Siberia involves encounters with the Soviet Air Force. Journeys in open cockpits have you shivering and shaking in instinctive sympathy as Beverley ploughs on over frozen rivers, jagged mountains and endless prairies of snow. That hardy annual of boys’ stories - the attack of the starving wolves from out of the forest is given a new twist.

Later a full-scale battle between squadrons of Red Communist fighters and the pirate squadron leaves you uncertain about which side you want to win. Beverley finds a comradeship with the very men that he is meant to be defeating and a champion in the man who earlier he believed wanted to kill him.

Yet all of this is just a prelude to the climax where the only man who can wreck the Flying Beetle’s plans is Beverley himself!

The story holds you to the end – in spite of the exaggerated characters and the “world-domination” plot. You are left with the tragedy of Harry Davies, “one whose gallant soul has gone to meet the greatest Dawn of all.” It was inevitable perhaps that even as Rochester called out like Browning’s Knight Roland that all was “Lost, lost !” the first clamours came in to bring the Beetle back to life.

But that’s another story

Porson’s Flying Service (Published by the Popular Library, London.)

This 1935 book seems to catch the essence of an even earlier age. It is essentially a collection of short stories strung together around the concept of a young man determined to make his way in the world and eventually found his own airline. The odds against him seem formidable – he has started his great enterprise with just a Maurice Farman biplane.

“Remember it had been built in the dark ages of flying, but by a great pioneer. It was a cumbersome-looking machine, yet its bamboo framework body gave to it a certain air of frailty. It was practically a glider, fitted with a 35 horse-power Green engine driven by a pusher propeller.”

It cost George Porson just £10. This price would seem to indicate that this book is a re-working or even a reprinting of “Porson’s £10 Plane” that was published in 1930.

George’s father is off big-game hunting in Africa but his Aunt Elizabeth is there to ensure that the seventeen year old doesn’t waste his time on an impossible venture. She has arranged for him to join a bank run by Messrs. Grubbins and Grime (That sounds a promising career !) and, peering at him severely through her lorgnette, tries to make him bow to her will. He will not get a penny from her when his business goes bust.

“’I shall not fail !’ replied Porson, with sublime confidence.” His first attempt to win some money to keep going occurs at Tuttleberry-cum-Hacklehurst when he enters a competition run by the local flying club. Up against a “frightfully posh sort of crowd”, who fly up to date Avro Avians and Blackburn Bluebirds, he succeeds in winning the game of flying golf by dropping his sand-bomb within a yard of the target. His slow flying machine actually gave him an advantage. One of the snobby “toffs” had called him a “flying pauper” but has to pay off a bet he made by becoming Porson’s mechanic and helper for a week.

The adventures that follow are suitably diverse and include catching a country-house thief who uses a balloon as a means of getaway, chasing a runaway tiger with a mad aristocrat on board, catching poachers, and making sure that a prize hen gets safely to a poultry show !

Porson’s companions include his little dog, Bill, who always jumps on board the Farman just before take-off. He is also on good terms with Gaffer, a local member of the working classes, who proves to be the “salt of the earth”.

Amongst the most amusing incidents is the one concerning the test parachute where it appears one of George’s fattish passengers is hell-bent on suicide. At the other extreme Rochester suddenly achieves a remarkable change of tone in the chapter “Taking it out of Cuthbert” where Cuthbert Crawford-Carter who had sneered at WW1 pilots is suddenly confronted by his own failure to fly the Farman properly. George’s friend, Woolerton, then tackles Cuthbert with an even more unpleasant accusation:

“Did you know, you beast, with your sneering talk of the old War pilots, that Porson’s brother was a War pilot – that he died in France ? And did you know how he died ?”

It turns out that that Porson’s elder brother had stuck with a riddled and blazing machine in order to save his observer who was wounded in the rear cockpit. And the name of the observer who survived was that of Cuthbert’s own brother. Woolerton finishes with, “And Porson never told you – although he knew.”

Elsewhere in the stories there are accounts of snobs and toffs getting their come-uppance, though some of George’s friends also prove to be first-class chaps even though they have titles. At times it is rather like P.G.Wodehouse’s Bertie Wooster had bought an aeroplane and the entire Drones Club had taken upflying.

However, there are also plenty of flying sequences with the Farman constantly on the brink of disaster and some very good birds-eye view descriptions of countryside. There are also four illustrations by Stanley Orton Bradshaw. Each one is black and white and the best is the frontispiece which shows the Maurice Farman in a steep dive just above the metals of a railway line with a train thundering towards the point of impact. To find out what happens you must read the book.

It must be admitted that the plotting and characterisation are superficial but the aeroplane details and the liveliness of the writing give the promise of something better to come.

George E. Rochester

Sunday, 12 April 2009

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)